Someone’s sitting in the shade today because someone planted a tree a long time ago. — Warren Buffett

For the Pritzker family, that tree was planted by Nicholas J. Pritzker.

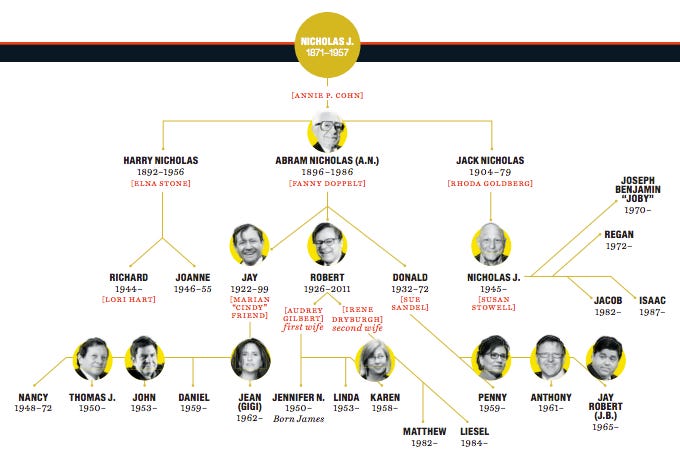

While his grandsons Jay (the financier) and Bob (the operator) are often credited with the family’s vast wealth, and his son A.N. was the first real dealmaker,1 Nicholas played a different, but arguably more fundamental, role. It’s not a story of high profile deals but of perseverance through relentless hardship and tragedy, pieced together from an autobiography he wrote entirely from memory.

He was the family’s first lawyer and, inspired by the Rothschilds’ centuries of success, unified the family’s assets under a shared ethos that would define the family for nearly a century.

Background

Pritzker family oral history traces their ancestry to the Khazars – a Turkic people who established a commercial empire between the 6th and 10th centuries and, notably, whose ruling class converted to Judaism. Legend is that a direct ancestor called Der Pritzker, living in the village of Pritzk, adopted the surname in the 17th century when Jews were compelled to take family names.

Nicholas's father, Jacob, was born in 1831. A small man – standing around five feet two inches and never exceeding 120 pounds – Jacob was blind in his right eye from an early injury. His life revolved around faith, family, honor, and honesty. In Kiev, then part of the Russian Empire, Jacob was a grain merchant. This was a common trade supported by the expanding network of railroads built in the late 1860s, which connected Kiev, Moscow and the major port in Odessa, where grain was a critical export.

Despite his diligence, Jacob was never a financial success, his honesty and trust in others often betrayed him. This led Nicholas's mother, Sophia, to join Jacob in business to help support their family.

Modest Beginnings

Nicholas was born July 19, 1871. His earliest memory of home was a two-story building with two rooms, dirt floors, no plumbing and an outhouse. Kiev was divided into the upper part called Kreschatik – home to the wealthy – and the lower part called Bolonia, which bordered the Dnieper River and was where the Pritzkers lived.

Life for the Pritzkers – Nicholas had five siblings – was frugal, with coarse food and hand-me-down clothes. However, no expense was spared on education – whether musical, scholastic or religious. Toys were nonexistent, with his parents considering them culturally worthless and a waste of time. His only toy growing up was a single homemade ice skate made with an old steel knife blade hammered into a piece of wood cut to the shape of his foot. This lone amusement ended when his father learned Nicholas had collided with a wagon.

Nicholas’s education began at age four at a Hebrew school where he studied the Torah, Rashi, Hebrew grammar, Psalms, and later, Gomorrah (Law). His brothers also tutored him – Abram teaching him Latin, Russian, German, and arithmetic, while Louis would practice his own lessons with Nicholas at night on their makeshift bed atop six chairs.

The Political Landscape

At the time, Russia was an autocratic state where the Tsar had absolute power, making and changing laws by simple decree. Local authorities could punish “dangerous” political offenders without trials with common penalties of imprisonment or exile to Siberia. Nicholas even mentioned the “brick sack,” described as a roofless circular brick structure built around a prisoner with a small hole to provide just enough food and water to sustain the accused while they rotted to death. I’ve found little to confirm the latter punishment, but unsurprisingly, this system fostered fear and corruption.

The government suppressed any socialist movements that wanted constitutional reforms. Basic education, like teaching peasants how to tell time, was considered dangerous and was a borderline criminal offense. Restrictions like these created a growing frustration with autocratic rule, leading to a period of escalating revolutionary activity and severe state repression starting in the late 1860s. This culminated with assassinations of high ranking officials and ultimately Tsar Alexander II in 1881. Nicholas wrote,

I was soon to learn that tragic times were upon us, that increasing misfortune was to be our lot for many years to come…

In 1880, Nicholas’s older brother, Abram – around twenty years old – was arrested for political treason after getting caught with uncensored pamphlets. His brother Louis, thirteen, was also briefly detained. Knowing the police would search Abram’s room, Jacob barred the front door of their home, gathered a printing press (just possessing one was a serious crime) and other materials from Abram’s room. He then jumped out the back window and dumped everything in the outhouse within minutes of police breaking through the front door.

Nicholas's mother then went through a series of desperate efforts to save Abram. She "tearfully and pathetically pleaded for the life and liberty of her boy Abram" to anyone with influence. Her persistence paid off – Abram’s life sentence to exile in Siberia was reduced to eighteen months under police surveillance in Kiev.

But, when Tsar Alexander II was assassinated and Alexander III took power, new edicts meant Abram’s case could be reopened and resentenced. The family also knew Abram, high-tempered and with a strong sense of honor, was unlikely to maintain the good behavior expected during his probation.

The Pogroms

In 1881, following the assassination of Tsar Alexander II, antisemitism gave way to pogroms (organized attacks against Jewish communities). One day Nicholas left his school to find the streets of Kiev filling with “ominous” crowds, many carrying wooden clubs or iron bars. He wrote,

Intuitively I knew it boded ill for me, so I rushed home as speedily as the crowded areas would permit, using where possible side streets...

He was not quite ten years old.

The Pritzker family lived in a second-floor flat within a courtyard building. Arriving at the heavy wooden gates, Nicholas was met by a crowd, within which someone yelled, 'get the little Jew.'" Jacob, "suddenly appeared at the gate, grabbed me, jerked me in,” and bolted the door, receiving a blow to the head in the process.

For the next sixty hours, Nicholas, his parents, and his siblings hid in an attic.

All night we heard, and all day we saw, the howling mob destroying property belonging to those of my father's faith.

Their own store was ransacked late Saturday night. Nicholas remembered their Christian landlord who, "at risk of his own life and freedom, defended us from the mob."

When the mob receded and the Pritzkers came down from the attic, they found their property wrecked. This experience, coupled with the political landscape (particularly concerning Nicholas’s older brother Abram who breached several conditions of his parole) was an inflection point in the Pritzker family story. Jacob committed to get his family out of the country.

The Pritzker family’s experience was not an isolated event but part of a wave of anti-Jewish violence that swept across Southern Russia following the assassination of Tsar Alexander II, for which Jews were falsely blamed (for malicious and political reasons). In the following decades, more pogroms would take place, fueling mass migration of approximately two million Jews from the Russian Empire.

Leaving Russia

The decision to leave Russia was difficult. The pogrom strained the family's already nominal finances, leaving little to fund traveling, let alone to establish themselves wherever they ended up. Jacob initially decided on France, believing it offered better opportunities for Abram. Abram himself was reluctant to leave, wishing to fight against the tyranny in Russia. However, he was eventually persuaded by fear of potential repercussions his actions posed to his family.

In August 1881, the family got their travel passports, except Abram. His anticipated departure, Nicholas claimed, would have caused issues for the whole family with the government. Jacob and Nicholas left Kiev for Brody, Austria, then a significant Jewish center sometimes called the "Jerusalem of Austria-Hungary" due to its commercial importance and large Jewish population, which became a major refuge for Jews fleeing Russian pogroms.

Abram arrived a day later wearing almost nothing, having been robbed by both the smuggler and the border patrol of nearly everything. Despite this, the family felt relieved Abram was out of Russia.2

In Brody, they heard tales of America from the Société Universelle, an international Jewish charitable organization.

Unbelievable stories that the Jew was, before the law, the equal of all other citizens! That his vote had equal power to change the laws! That a man in America was eligible to engage in any business, profession or occupation, even to the tilling of the soil, on equal terms with all without regard to his or his ancestor’s faith! Impossible, of course, it seemed to us; but how sweet to hear of such heavenly Utopia!

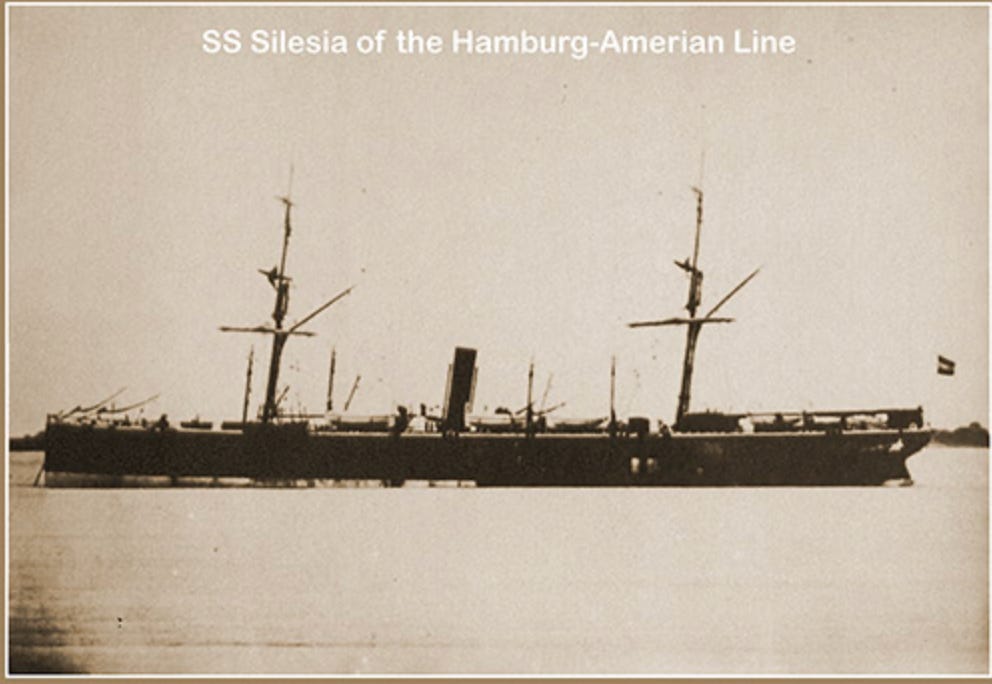

So, in October 18813 Nicholas, Jacob, and Abram took a passenger train from Brody to Hamburg, where they boarded the steamer Silesia for America. Nicholas wrote it was, “...apparently not intended for ocean passenger travel," and, "this was to be her last and only trip as such."4

They traveled in steerage, with improvised tiered bunks in the hold, for a distressing 21 days. Nicholas spent many nights on deck, "drenched by the overlapping waves." It was during this time they learned that English, not German or French as they had been told, was the official language of America.

They landed at Castle Garden in New York Harbor in late October 1881 and slept on the floor for five days. Through the Société Universelle, they received train tickets to Clinton, Iowa, a destination chosen by chance, not choice. They arrived early November 1881, but realized the small town offered no prospects, confirmed by the only other Jewish family there. Abram worked for a day at a sawmill for fifty cents, labor that pained Jacob to see his oldest son work. Defeated, they traveled to Chicago.

Chicago

At the time, Chicago was booming. Its population grew tenfold to 1.1 million people from 1860-1890, fueled by the combination of economic growth and immigration. Chicago was essential to the American West economy, being considered the “most important node in the American railroad system.” Chicago & North Western Railway, a major railroad operator, highlighted this centrality with the construction of its Wells Street Depot.

Nicholas, along with his father and brother, ended up at the Harrison Hotel. However, Nicholas soon contracted a cold, exacerbated by an unheated room. This led to his admission to the Michael Reese Hospital, becoming one of its first three patients. He spent six weeks there, his clothes burned upon admission, but left, "clad in a brand new suit of clothes5... 10 cents for carfare and the sum of $1.00 with which to start my business career" from Dr. Otto Schmidt.

With the dollar from Dr. Schmidt, Nicholas – ten years old – launched his first venture: shoe shining and selling newspapers. His first newspaper inventory cost 23 cents more than he had, a loan “easily negotiated.” He described the routine:

3:00 a.m.: Wake up and pick up newspapers

5:00 a.m.: Arrive at designated stand

8:00 a.m.: Sleep or study English by reading newspapers with English-German and German-Russian dictionaries for translation

6:00 p.m.: Sell the evening newspaper

7:00 - 9:30 p.m.: attend evening classes at Jones School

On cold nights, he slept in the LaSalle Street tunnel, packing newspapers around his chest, legs and wrists. Newspaper would stick to his bloody shins and wrists (due to severe chapping). He wrote that these early wounds almost cost him his left leg in 1939 from long-term circulatory and neurological damage.

His father, Jacob, sold matches and shoestrings from a basket door to door. Abram worked in a cutlery factory until an injury to his hand led to his dismissal under the guise of negligence. Then, in a continuing callous twist of fortune, Nicholas received a small windfall…all he had to do was get hit by a “tandem” (whether a horse-pulled wagon or a bicycle is unclear). The driver paid Nicholas a silver dollar, which he used to buy his father and brother their first meal in days.

In June 1882, Nicholas’s mother, Sophia, and his sisters arrived in Chicago – despite Sophia first pleading that Jacob, Abram and Nicholas return to Russia instead – and the family was reunited, living in a basement. Despite having little but a free portion of the floor, they always offered to temporarily house other immigrants, embodying the principle, “When a wayfarer comes to the door, take him in…”

Their struggles continued: Nicholas was robbed in an alley, and Jacob’s business partner – who he’d recently gone into business with – disappeared with most of the partnership's assets. Then, in March 1883, Nicholas’s brother, Abram (the one who had been arrested in Russia), committed suicide. The loss had a devastating effect on the family. His mother, filled with grief, wanted to return to Kiev.

Taking advantage of a railroad price war that dropped tickets to New York to $1, she took the children there. Upon arrival, news of another pogrom in Russia reached them, and they decided to settle in New York, in a sixth-floor flat at 276 Madison Street.

In New York, Nicholas began studying with a druggist who tutored him in arithmetic, decimals, fractions, and basic algebra, while Nicholas worked as a Western Union telegraph boy. By summer of the following year, Jacob Pritzker had prospered in Chicago and brought the family back, settling them into a five-room flat on Bunker Street. In fall 1884, Nicholas enrolled in the Foster School, placed in the fourth grade, and by summer 1885, he had passed the seventh grade.

During this period, the family, along with other early refugees who had made progress, turned to aiding newer, poverty-stricken immigrants. His mother formed a nickel society, where members contributed five cents a week for new arrivals. Men offered small, interest-free loans to help others establish themselves.

The Path to Law

In 1885, Jacob opened a store on State Street, and Nicholas, while working as an errand boy in the U.S. Stockyards for $3 a week and attending high school classes five nights a week, felt a growing desire to become a lawyer.

He wrote,

My own ambition was Law. To sit in fair judgement between man and his fellow, in the solution of his domestic connections and with the State!

By no means were my dreams of success to be purely professional! Ah no. On the contrary, wealth, vivid position, social and even political prestige were within the scope of my attainment! That is a very human and lawful ambition in free America and to that end I have since strived.

He recognized the burden of their poverty, especially on the women in his family, and felt a profound responsibility:

Wealth? Yes! I know that I must have that too... The chill penury of our manner of life was telling upon us all... I knew I was the only one in the family to correct the situation... The responsibility was upon my shoulders. Yes, I must have wealth, seek a more profitable occupation.

By the summer of 1888, he met a public library board member and secured a job at the library. The pay was small, but it offered plenty of time to study. He supplemented this by bookkeeping for small tradesmen and teaching at night.

Then Nicholas met Annie Cohen. Their romance was immediate, but Annie's family sent her back to Milwaukee after learning of the relationship. They corresponded, though Nicholas expressed doubts about their future due to his need to focus on work. A family friend suggested studying pharmacy where owning a drugstore run by clerks could provide income while he pursued his ambition of law.

In spring 1889, he began as "the boy" at a drugstore for $3 a week, cleaning and assisting with chemical preparations. "In those days a pharmacist took pride in making for himself such drugs and chemicals as did not require extensive manufacturing plants," he noted.

He enrolled in the Chicago College of Pharmacy (now part of the University of Illinois) in the fall of 1890. But by Thanksgiving 1891, he owed the college $20 before he could attend any more classes. He had less than $3. He refused to ask family for help, a resolve he maintained throughout his life.

A turn of luck at a Thanksgiving turkey raffle hosted by a bar, where his boss took him to meet with clients, earned him $4. The next day, the same clients played Nicholas in a game of quarters, and by Monday, Nicholas had his tuition money. However, some practical joke by these men led to Nicholas losing his job. He found another and finished his first year of school.

Nicholas and Annie ultimately married but job instability continued; he was fired for "laziness" after two months from one position. Despite these setbacks, he continued in his pharmaceutical studies. He was admitted to the first practical examination ever given in the state and passed as a fully registered pharmacist. In a later speech, Nicholas’s son, Abram Nicholas Pritzker (usually referred to as A.N.) said Nicholas received the 8th pharmacist license issued by the state of Illinois.

This success, however, didn't immediately translate to stability. He took a job as chief clerk in a Des Moines, Iowa drugstore, which he soon learned was a front for wholesale liquor sales during Iowa's prohibition where liquor could only be sold via a pharmacist's prescription. "Highest state officials and judges of higher courts were patrons of the bar in a basement room."

Nicholas's involvement was minimal until he was told to sign a bi-monthly affidavit swearing, falsely, that the alcohol was for external/medicinal use only. He refused, and his job ended, though he consented to sign one perjured return to protect his former employer.

He returned to Chicago, and his first son, Harry, was born on August 1, 1892. The pressure of providing for his family weighed on him, and he determined that his children "should have a systematic, complete and thorough education." Believing he wouldn’t be able to move on to law from pharmacy, he focused on perfecting his chemistry skills, conducting original research (some published in the Druggist Technical Journal), and even spoke at the International Session of Pharmacists at the 1893 World's Fair.

In 1894, he loaned his savings and borrowed money to help a man named Sampson Leviash start a small cigar factory, a business Leviash continued until his retirement in 1931. It’s unclear if this ever provided any financial benefit to Nicholas, but they were good friends until Sampson’s death in 1939, and it appears they may have practiced law together at one point early on.

Nicholas then ventured into owning drugstores himself, first buying a place at Burnham's and renting a store at Division and Paulina, then selling that and buying another at Halsted and Taylor. These businesses were unsuccessful. "From these ventures I soon learned that I lacked ability to conduct any retail business," he confessed, citing unfit temperament to deal with the unreasonableness of customers.

What Nicholas omitted in his autobiography, according to an October 1895 article in The Pharmaceutical Era, was he was defrauded in a real estate trade with the Halsted property and ultimately had the man arrested.

Soon he "sold out, paid my debts and once more was left totally penniless and without a job." Another child, Abram Nicholas (A.N.), was expected the following January, and he couldn't find work as a druggist that paid a living wage. He tried selling cigars for a few weeks without a single instance of success. Then, tragedy struck again when his sister Sarah, unhappy in her marriage and life, committed suicide in August 1895.

Meanwhile, Nicholas lamented,

Again I was without funds, nor was there any source from which to obtain financial assistance... desperation almost overtook me. But I had been through so many of these economic depressions, that pain left me callous.

His father, whose health declined considerably after news of Sarah, passed away in January 1896. Hardship didn’t relent as they endured the "business panic of 1896," which Nicholas described as "the worst during my experience." His mother received about $1,000 net from Jacob's estate after debts and heavily mortgaged properties were dealt with. She entrusted this to Nicholas, who provided her with a monthly allowance, initially $100, rising to $275 in her final years. He maintained a fiction that this came from "lucrative investments" he made for her, though much of it was paid out of his own pocket.

Law

Forced by circumstances, Nicholas had reluctantly entered the “trimming” business in 1895. He disliked the business, felt an "inferiority complex," and knew he was "whipped before I started." He preferred to read American history than learn about silk prices. The business struggled, debts mounted, and his ever present ambition to study law seemed to be slipping away.

He called a creditor about buying Nicholas out, but the creditor and accountant reviewed the books and explained that the business was “hopelessly insolvent.” Here, Nicholas faced a dilemma that afterwards caused him “terrific penalty in mental anguish and shame.” He had to choose between his duty to his family and his duty to his creditors.

By turning over whatever he had to pay debts, creditors would only get a fraction of what they were owed and he would be bankrupt, unable to support his wife and children. So, Nicholas made a fraudulent conveyance of the business. He transferred the business assets to someone else (usually a close relation or trusted party), leaving himself personally liable for the debts but with nothing for creditors to seize.

From the perspective of the creditor, this type of illegal maneuver wasn’t typically worth pursuing in court to void the transfer, knowing that they would bear the full burden of proof (in a time with no digital records), and be throwing good money after bad.

Knowing Nicholas’s credit was gone, he finally enrolled at the Illinois College of Law on November 1, 1900. He supplemented his limited pre-legal education by reading Ridpath's History of the World and the Encyclopaedia Britannica. He attended classes every evening and Saturday afternoons, doubling his workload to finish his course sooner, all while living on a strict budget, often supplementing meals with coffee and a sugar pretzel.

The day of his bar examination approached in May 1902. He felt immense pressure, unsure what type of job he could find to support his family if he didn’t pass. Despite severe headaches and toothaches6, he studied relentlessly. His wife, Annie, supported him throughout. He passed, ranking sixth in a class of over seventy.

Realizing his practical knowledge was lacking, he spent his time in court clerks' offices, reading pleadings, orders, deeds, and contracts to familiarize himself with legal practice. His early cases were varied, including bankruptcies, real estate transactions, and a challenging criminal defense where he successfully appealed a wrongful conviction at a personal cost of $700. Ironically, he also gained clients from his creditors who offered a retainer and 10% of collections made, a line of business he didn’t pursue long.

“The Chicle Case”

The Chicle Case was a peculiar account. If you don’t know, chicle is a natural gum that used to be used to manufacture chewing gum. Here’s how Nicholas described the events.

A prominent Salt Lake City attorney came to Nicholas and said their client wanted to get access to a chewing gum manufacturer's books in order to find a secret formula they believed one of two officers in the company had.

Nicholas saw no legal reason to compel the corporation to open their books up, so declined the case.

Peculiarity #1: That same day, a Chicago client brought Nicholas a $1,200 collection against that same chewing gum corporation, saying no assets could be found and the two officers – referred to by Nicholas as “Mr. A” and “Mr. W” – couldn’t be reached.

Nicholas went back to the Salt Lake City attorney and suggested filing for an involuntary bankruptcy proceeding which would legally require the company to provide access to everything.

So, that’s what Nicholas did. Except the officers couldn’t be served because they couldn’t be found. Mr. A was supposedly living in Niagara, NY and Mr. W out of town.

Peculiarity #2: Nicholas then gets a phone call and apparently finds himself on a crossed wire, overhearing Mr. W talking with his attorneys, and mentioning that Mr. A was staying at the Congress Hotel.

Nicholas serves both men, and Mr. W testified he had no knowledge of where the requested books were.

Peculiarity #3: Nicholas gets another mystery call saying the books are in Mr. W’s office vault.

So Nicholas sends a marshall to the office and breaks into the vault and gets the books.

Mr. A was reportedly in his 70s and had recently lost a $10M fortune through an expensive second wife. Mr. W, caught falsely testifying about the records, ended up paying all fees and debts of the chewing gum company. Nicholas’s clients got the secret formula they were after.

Mr. W, impressed with Nicholas, became Nicholas’s client for the rest of Mr. W’s life, and Nicholas represented his family in ‘many important cases’ after Mr. W’s death.

I haven’t determined whether these events were coincidental or a more orchestrated effort by an unknown party. Either way, the case was notable.7 The fact that a prominent attorney sought out Nicholas’s help highlighted his quickly growing reputation as he continued a full workload of diverse cases.

Financial Difficulties

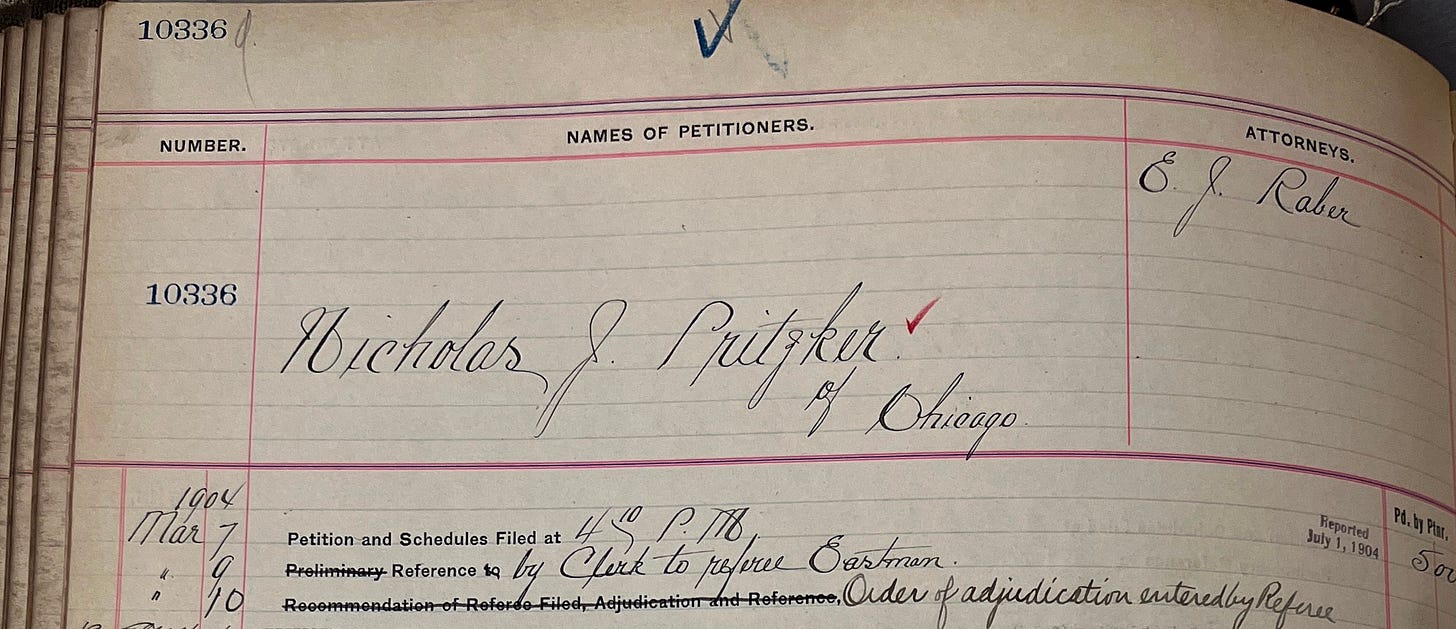

In his first full year of practice, Nicholas earned $3,800 (~$140k in 2025 dollars). Meanwhile, one of his “under-handed sneaky hypocrite” classmates had entered the collections and bankruptcy practice. At some point Nicholas had “curtly” refused some unstated proposition from his classmate, so the man decided to get a list of Nicholas’s creditors from his previous business dealings years earlier and persecute Nicholas.

A State’s Attorney offered to indict the classmate and have him disbarred, but Nicholas abstained. A court officer, in the process of seizing Nicholas’s desk to satisfy a debt, felt bad and decided to pay the collection in full (with Nicholas’s promise to repay him). This officer became a friend and client of Nicholas’s and even signed a $1,600 appeal bond in another judgement against Nicholas.

The vindictive classmate and Nicholas finally met at court, where the classmate said if Nicholas ceased to, “treat him as a dog he would quit.” Nicholas, in a fine show of diplomacy, said that was an insult to dogs and would from then on treat the classmate as a skunk.

While he doesn’t mention it in his book, Nicholas ultimately filed for bankruptcy in 1904 (while also representing someone filing for bankruptcy).

Though his income decreased to $3,400 his second year of practice, with his balance sheet finally cleaned up, the foundation for the Pritzker fortune was set. His income increased steadily thereafter, earning $33,000 (~$610k in 2025 dollars) by 1919. He remained above that level until his sons joined the practice in 1921.

Legacy

Nicholas’s autobiography ends in 1941, but he lived until 1957 practicing law and engaging in philanthropy. Ownership filings and some publications suggest his involvement in some of the family’s business dealings, likely in an advisory capacity to his son, A.N.

Nicholas’s life was filled with perseverance against relentless poverty, persecution, and tragedy. His determination, love for family, and belief in the opportunities provided in America laid the foundation that would enable future generations of Pritzkers to achieve one of the world's great fortunes.

From a young age, Nicholas worked tirelessly for a better life. Even as an attorney, he worked seven days a week, sometimes into the early hours of the morning. He took no vacation in thirty-seven years except for one business trip to California and a ten-day trip East. One motivation for this was to have a prosperous law practice for his children to join, which they did.

For generations – from Nicholas to A.N. to Jay and Bob – the family operated as a single unit. It’s a theme we’ll encounter time and again.

While A.N., Jay and Bob receive most of the credit for the family’s ethos and wealth, Nicholas initiated it around 1920,

...with the goal that we become equal partners for life, I declared all my possessions (then about one-quarter of a million, well-invested [$4M in 2025 dollars]) as common property among all four8 of us. A communistic rule we established: ‘For each, according to his ability, to each, according to his need.’ Thus while all share equally in accumulation, salaries are unequal, as marital status and other circumstances may dictate.

My own worth, such as it is, my standing in the community, the clients whose faith in me has passed on to my sons, these have also paved the way for an entree cordial for business connections…To the increased economic welfare of the family, I claim no credit, subject only to the fact that Abram has built on the beginnings I made.

And here I want to register the hope that this family unity may in all respects continue for their lives, to be passed on for emulation by my grandsons! I could here repeat Anselm Rothschild’s advice to his sons and the success of that family, or the fable by Krilov, of the father and his seven sons and seven reeds: Each held separately, could easily be broken, but when united no one could break any one of the seven.

Of course, to succeed each must keep the honor of all untarnished!

By 1924, Nicholas – along with, we can assume, his sons – was acquiring assets like 18 apartments for $91,000 ($1.7M in 2025 dollars), $69,000 of which was mortgaged.

As a crude approximation, from 1920 to 2024, the Pritzker family’s combined net worth compounded at approximately 12.3%. For reference, the S&P 5009 (including dividends) did ~10.5% during the same period. That 1.75 percentage point difference created a family fortune (albeit presently divided among many heirs) worth ~$42 billion, ~$34B greater than if it had compounded at the S&P 500’s rate (figures are approximate due to rounding and the effects of compounding over a century).

And in future articles we’re going to begin breaking down how they did it.

Thank you to everyone who is already supporting this project.

If you’d like to support it in a small way, you can share this article with others or buy me a coffee here.

If you’d like to support it in a big way, consider becoming a paid subscriber (you can find out more on the about page)!

Sources & Further Readings

Pritzker, Nicholas J. Three Score After Ten. 1941.

JewishGen Yizkor Book Project: Brody, Ukraine (An Eternal Light: Brody, in Memoriam)

https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/e/collections/maps/chifire/home.html

A.N. Pritzker Speech

From Nicholas’s autobiography, he stated,

From the beginning I could see that Abram was not to be the bookworm, the reviewing court brief-writer that I had expected him to be. He had financial ambitions; and for it he showed remarkable aptitude. His keen understanding of figures, of mathematics, he was employing to the full extent. Another thought he propounded:

‘Why earn for your client large profits for a mere pittance, often resentfully given, when by the same effort and with additional understanding one can gain the whole return for his ability?’

Nicholas wrote that the entire family received travel passports, excluding Abram, whose planned departure would have endangered them all. However, the whole family never planned to leave Kiev simultaneously. Jacob and Nicholas left first, with Abram being smuggled out soon after. The remainder of the family stayed behind until the first three could establish themselves somewhere.

So, why did the remaining family in Kiev not face repercussions when Abram, who was on probation and required to report to the police twice per day, stopped appearing? His disappearance following the issuance of travel passports to the rest of his family and departure of some would have made for an easy explanation that he left illegally. If his family knowing he was going to leave would have gotten them all in trouble, surely the fact that he actually did leave would have caused the same (or worse) consequences to the family members who stayed behind.

Nicholas’s February 11, 1957 obituary in the Chicago Daily Tribune reported he arrived in Chicago in 1879 and began practicing law in 1900, not 1881 and 1902, respectively, as he remembered in his autobiography. Given the timeline of Russian pogroms and a 1902 announcement in The American Lawyer of Nicholas’s admittance to practice law, I’m inclined to believe the obituary was incorrect on both accounts.

Neither of those points seem accurate based on what I’ve read on the SS Silesia which made many passenger trips.

If you ever research the Pritzkers, you’ll inevitably come across articles and/or quotes from the family about Nicholas being given a coat by the hospital that the family has been paying for ever since (through donations).

They felt sorry for him and bought him an overcoat for $10.00 which we are still paying for. — A.N. Pritzker

Yet, Nicholas wrote,

Upon my admission to the hospital, all my clothes, excepting (my emphasis added) an adult size spring overcoat, the gift of Chertov while in Kiev, and an earflapped cap, were burned. A very good idea! For behold me, leaving Michael Reese clad in a brand new suit of clothes, stylishly cut, with long trousers, which had been given to me…

This is a trivial detail, but a nontrivial point. Oftentimes one person reports something, and everyone else runs with it without ever verifying. Even amongst points about the family said by the family, it’s important to trust but verify.

At least twice he had to have teeth extracted. Without being able to afford having it done properly (ie professionally, and with something to numb the pain) he once convinced a dental student pull a tooth. It broke off, and he didn’t get the rest of it removed until much later in life.

The other time he entrusted a street performer who claimed to the crowd that he could pull teeth without causing pain. Nicholas’s screams were apparently drowned out by a band that played during the “procedure.”

There are some interesting possibilities in identifying some of these redacted parties, which I might cover in a future article.

The four being Nicholas and his three sons: Abram (A.N.), Harry and Jack.

S&P 500 returns (including dividends) sourced from Robert Shiller and Yahoo Finance. See Chapter 26 of Robert Shiller’s book Market Volatility (1989) for more information on the data series.

2024 is the latest Forbes has updated the Pritzker family's net worth.

© 2025 Rockwood Notes LLC. All rights reserved.

Awesome history with incredible details, thank you !

Minor issues that could use correction: Kiev’s district where they resided was and is called Obolon’, not Bolonia; and the boy was studying Gemora, decidedly not Gomorrah. My family lore shares a lot of geography here, at least in the first third.

This is fantastic. I’m looking forward to following along as you publish more exceptional research.